The process of making cheese has been around for thousands of years, with the original cheese dating back around 5,000 years. Today, there are over 2,000 varieties of cheese, each with its own unique flavour and texture. In the UK, the majority of cheese is made from vegetarian-friendly, non-animal rennet and good-quality milk. The milk is then pasteurised to kill any bacteria and cooled before being pumped into large cheese vats. Starter cultures are added to the milk, which is then separated into curds and whey. The curds are cut into small pieces, stacked, and pressed to form a homogeneous texture. Finally, the cheese is removed from the moulds, cloth-bound, and matured for several weeks to months.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Pasteurisation

The process of pasteurisation involves heating the milk to a high temperature for a short period of time. This can be done by running the milk through hot stainless steel plates, or by heating a large pot of milk. The milk is heated to around 72°C for about 15 seconds, or to 65°C if using the Low-Temperature Long-Time (LTLT) pasteurisation technique. The milk is then rapidly cooled to approximately 32°C, at which point starter cultures are introduced.

Some cheeses are made from pasteurised milk, while others are made from unpasteurised or 'raw' milk. Pasteurisation is considered more efficient on a large scale, as there is less need for care during the milk collection stage. It also extends the shelf life of dairy products. However, it kills the good bacteria that give raw milk cheeses their unique, complex flavours.

Unpasteurised cheese is generally made by smaller, artisanal producers who are following traditional methods. To make unpasteurised cheese, the milk is heated to around 30°C, which is just enough to allow the milk to start fermenting and eventually turn into cheese. Heat-treated cheese is made by heating the milk to approximately 55°C for about 15 seconds, which is considered a good balance between pasteurised and unpasteurised milk as it kills off dangerous bacteria while preserving most of the complex flavours.

The Magic Ingredients Behind Parmesan Cheese's Unique Flavor

You may want to see also

Rennet

The process of extracting rennet from calf stomachs involves slicing the dried and cleaned stomachs into small pieces and soaking them in salt water or whey, along with vinegar or wine to lower the pH. After allowing the solution to sit for a period of time, it is then filtered, leaving behind crude rennet that can be used for coagulating milk. This type of rennet, known as animal rennet, is considered the most traditional method for cheesemaking.

However, due to the limited availability of mammalian stomachs and the desire to explore alternative sources, cheese makers have also turned to other options for obtaining rennet. These alternatives include microbial sources, as well as plants and fungi. For example, Homer's "Iliad" suggests that the ancient Greeks may have used fig juice for coagulating milk. Other plant sources with coagulating properties include dried caper leaves, nettles, thistles, mallow, and several species of Galium.

Today, most cheese is produced using chymosin, the key component of rennet, derived from bacterial sources. This method is more common in industrial cheesemaking due to its lower cost compared to animal rennet. The use of fermentation-produced chymosin allows for the creation of a wide range of cheeses, including those suitable for vegetarians and those adhering to Kosher and Halal dietary restrictions.

Cheese Cultures: How Are They Made?

You may want to see also

Cultures

There are many different types of starter cultures, and the specific culture used will depend on the type of cheese being made and the flavour profile desired. For example, to produce a white rind, such as on a Brie or Camembert, you would add Penicillium Camemberti. Blue cheeses, on the other hand, are typically ripened using Penicillium Roqueforti. The temperature of the milk when adding the cultures is crucial, as too high a temperature will kill the bacteria, while too low a temperature will prevent them from activating. For most cheeses, the milk temperature is maintained between 30°C and 35°C, although certain cultures, such as those used to make Emmental, require warmer temperatures.

The addition of starter cultures is a critical step in cheesemaking, as it not only initiates the transformation of milk into cheese but also contributes to the development of the cheese's flavour. The type of bacteria and the conditions under which they grow greatly influence the final taste and texture of the cheese.

By altering the starter culture and introducing different combinations of cultures, cheesemakers can create a vast array of cheese varieties. Each culture brings its unique characteristics to the cheese, resulting in diverse flavours, textures, and even appearances. This versatility in cheesemaking allows for endless experimentation and the creation of new and distinctive cheeses.

Daiya Cheddar Cheese: What's in This Vegan Treat?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ageing

The ageing process is a crucial step in cheesemaking, as it not only alters the texture of the cheese but also intensifies its flavour. The length of the ageing process depends on the type of cheese being made, with soft cheeses like Bath Soft Cheese ripening within three weeks, while hard cheeses like Wyfe of Bath can mature for up to one or two years. During the ageing process, the cheese loses moisture, and enzymes and bacteria are allowed to further develop, creating complex flavours.

The ageing time for cheese can vary from a few weeks to several months, or even longer. The longest-aged edible cheese, Bitto Storico, is matured for an impressive 18 years. The duration of ageing depends on the intended end product, with factors such as temperature and humidity playing a significant role. Most cheeses are typically matured in high humidity at around 10 degrees Celsius.

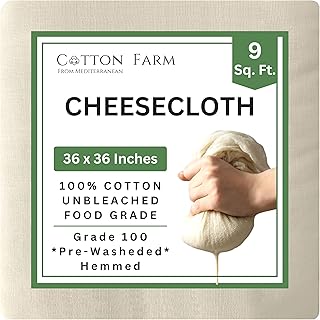

Cheeses can be wrapped in cloth, covered in wax, or left uncovered during the ageing process. Some varieties are rubbed with brine or other components. For traditional British cheese, the pressed curds are cloth-bound and then taken to a cool, humid store to mature. This maturation process can last from one to 15 months or even longer, depending on the desired characteristics of the final product.

The amount of rennet used, the speed of the set, and the nature of acidification by the starter bacteria are all factors that influence the ageing process and the final product. By altering these variables, cheesemakers can create a vast range of cheese types, from basic varieties to artisanal creations.

The ageing process is a delicate balance, as the temperature must be carefully controlled to ensure the bacteria remain active without being killed by excessive heat. This stage of cheesemaking requires patience and precision to ensure the desired flavour and texture profiles are achieved.

Muenster Cheese: A Simple Recipe for a Delicious Treat

You may want to see also

Milk types

Milk is the most important ingredient in cheese, and the type of milk used determines the kind of cheese produced. The four milk types that the FDA has deemed acceptable for cheesemaking are cow's milk, goat's milk, sheep's milk, and water buffalo milk. Each type of milk has a unique composition of water, lactose (milk sugar), protein, and fat, which gives the resulting cheese its distinct flavour and texture.

Cow's milk is the most common and affordable type of milk used for cheesemaking in the UK and worldwide. It typically contains 87-88% water, 5% lactose, 3.5–5% protein, and 3–5% fat. Cow's milk cheeses have a creamy, buttery, and smooth texture, with a range of flavours from grassy and sweet to earthy. They can be soft or hard and have an "off-white" hue due to cows' inability to process beta carotene in grasses. Examples of cow's milk cheeses from the UK include Cheddar, Red Windsor, and Caerphilly.

Goat's milk cheese has a distinctive white colour because goats can easily digest beta carotene found in grasses. Goat milk has lower lactose levels than other milk types, making it easier to digest. It also has the lowest fat content. Goat's milk cheese has a mildly acidic, zingy flavour that can develop a sweet caramel finish with age. Chèvre, a common goat's milk cheese, is often presented in a log shape and rolled in dried fruits, herbs, or spices. An example of a British goat's milk cheese is Harbourne Blue, produced in Devon.

Sheep's milk cheese is known for its striking flavour, as seen in the comparison between American supermarket feta and Essex Feta from Lesvos, Greece. Examples of sheep's milk cheeses from the UK include Fine Fettle Yorkshire, Parlick Fell, and Lanark Blue.

Water buffalo milk is the fourth type of milk recognised by the FDA for cheesemaking. While less common in the UK, it is used in other parts of the world to produce unique cheeses.

In addition to the type of milk, other factors that influence the style of cheese produced include the amount of rennet used, the speed of setting, and the nature of acidification by starter bacteria.

The Delicious Secret Behind Cooper Sharp Cheese

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first step in making cheese is to inspect the milk and then filter it. It is recommended that novice cheesemakers use pasteurised milk, which involves heating the milk to at least 71.7°C for a minimum of 15 seconds to kill any bacteria.

The process of turning milk into a solid involves removing excess water and acidifying the milk. The milk is encouraged to acidify by allowing bacteria to consume the lactose in the milk and turn it into lactic acid.

Rennet is an enzyme that is added to coagulate the milk and form curds. Rennet joins up the proteins in the milk to allow the milk to fully coagulate and form a firm, jelly-like substance.

Ageing intensifies the flavour of the cheese and alters its texture. The ageing process allows time for enzymes and bacteria to further develop.