Blue cheese is made using the fungus Penicillium, specifically the strain Penicillium roqueforti, which is responsible for its distinct taste, smell, and appearance. The fungus grows along the surface of the curd-air interface, creating the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese. The blue veins are also responsible for the aroma of blue cheese. The mold on blue cheese is from the same family of spores used to make penicillin.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Penicillium roqueforti |

| Common Name | Blue-cheese fungus |

| Texture | Chitinous |

| Color | Blue-green |

| Odor | Odd smell |

| Taste | Sharp flavor |

| Use | Production of blue cheeses, flavoring agents, antifungals, polysaccharides, proteases, and other enzymes |

| Growth Conditions | Dark, damp conditions |

| Temperature | 28°C |

| Toxin Production | Roquefortine C, mycophenolic acid, aflatoxin M1 mycotoxins, aristolochene, and PR toxin |

| Health Benefits | May contain anticancer properties |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Blue cheese is made using Penicillium roqueforti, a type of fungus

- This fungus is safe to consume and is related to the mould used to make penicillin

- Penicillium roqueforti produces enzymes that break down cheese proteins, creating a creamy texture

- It also triggers lipolysis, which gives blue cheese its distinct blue look, smell, and sharp flavour

- The fungus thrives in dairy environments and is used to make many types of blue cheese

Blue cheese is made using Penicillium roqueforti, a type of fungus

The first step in making blue cheese is to prepare a Penicillium roqueforti inoculum, which can be done using multiple methods. This involves using a freeze-dried Penicillium roqueforti culture, which is washed from pure culture agar plates and then frozen. This fungus can be found naturally, but today, cheese producers typically use commercially manufactured Penicillium roqueforti.

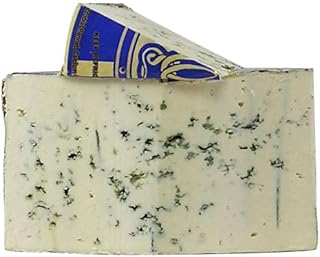

Once the inoculum is ready, it is added to the cheese after the curds have been drained and formed. Some blue cheeses are injected with spores before the curds form, while others have the spores mixed in with the curds. The curds are then pierced, creating air tunnels in the cheese. This step is crucial as it allows the Penicillium roqueforti to grow along the surface of the curd-air interface, forming the characteristic blue veins.

Penicillium roqueforti produces enzymes that break down the cheese's proteins, a process called proteolysis. This gives the cheese its creamy texture, especially near the blue veins where the enzymes are most active. Additionally, Penicillium roqueforti triggers another process called lipolysis, which leads to the creation of free fatty acids and the release of methyl ketone. This process contributes to the distinct blue colour, sharp flavour, and pungent smell of blue cheese.

The final step in making blue cheese is ripening, which involves ageing the cheese for a sufficient period. During this time, the temperature and humidity are carefully monitored to ensure the cheese develops optimal flavour and texture without spoilage. The ripening temperature is typically around eight to ten degrees Celsius, with a relative humidity of 85-95%.

Blue Cheese's Perfect Pairings: A Guide to Delicious Combinations

You may want to see also

This fungus is safe to consume and is related to the mould used to make penicillin

Blue cheese is made using Penicillium, a type of mould that is responsible for its distinct taste, smell, and appearance. The mould on blue cheese is from the same family of spores used to make penicillin, the antibiotic. The major industrial use of this fungus is the production of blue cheese, flavouring agents, antifungals, polysaccharides, proteases, and other enzymes.

The prevailing legend of blue cheese's discovery revolves around a happy accident. The story goes that, over a millennium ago, in the Rouergue region of southern France, a shepherd settled down in a cave for lunch. Before he could take a bite of his rye bread and sheep's milk cheese, his sheep got spooked and took off. The shepherd went after them, leaving his lunch behind. Months later, he passed by the same cave and found his lunch untouched, except for a thick layer of mould that had formed on top. Either out of curiosity or hunger, the shepherd took a bite.

The reason the shepherd didn't get sick is that the damp limestone caves of southern France are filled with naturally-occurring Penicillium roqueforti mould spores, which are safe for human consumption. In fact, most store-bought blue cheeses are made in hygienic production facilities that simulate these dark, damp conditions to prevent dangerous moulds, fungi, and bacteria from contaminating the cheese.

During the cheesemaking process, Penicillium is added after the curds have been drained and rolled into wheels. The Penicillium roqueforti creates the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese after the aged curds have been pierced, forming air tunnels in the cheese. When given oxygen, the mould grows along the surface of the curd-air interface. The veins along the blue cheese are also responsible for the aroma of blue cheese.

Green Olives, Blue Cheese: Healthy or Indulgent?

You may want to see also

Penicillium roqueforti produces enzymes that break down cheese proteins, creating a creamy texture

Blue cheese is made using Penicillium, a type of mould that is responsible for its unique taste, smell, and appearance. The mould on blue cheese is from the same family of spores used to make penicillin. The prevailing legend of blue cheese's discovery revolves around a happy accident. The story goes that, over a millennium ago, a shepherd in the Rouergue region of southern France left his lunch of rye bread and sheep's milk cheese in a cave while tending to his flock. When he returned months later, a thick layer of mould had formed on top. The damp limestone caves of southern France are filled with naturally occurring Penicillium roqueforti mould spores.

Penicillium roqueforti is the fungus that creates the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese. After the aged curds have been pierced, forming air tunnels in the cheese, the mould is able to grow along the surface of the curd-air interface. The veins along the blue cheese are also responsible for the aroma of blue cheese. In addition, Penicillium roqueforti triggers a biochemical event called lipolysis, which catalyses enzymes that lead to the creation of free fatty acids and the release of methyl ketone. This gives the cheese its distinct blue look, odd smell, and sharp flavour.

The major industrial use of this fungus is the production of blue cheeses, flavouring agents, antifungals, polysaccharides, proteases, and other enzymes. The fungus has been a constituent of Roquefort, Stilton, Danish blue, Cabrales, and other blue cheeses. Other blue cheeses, such as Gorgonzola, are made with Penicillium glaucum.

Blue Cheese Indica: What's the Verdict?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

It also triggers lipolysis, which gives blue cheese its distinct blue look, smell, and sharp flavour

Blue cheese is a type of cheese characterised by its creamy texture, strong scent, and tangy, sharp taste. The distinct blue veins in blue cheese are created by the Penicillium roqueforti fungus, which grows along the surface of the curd-air interface after the aged curds have been pierced, forming air tunnels in the cheese. The fungus produces volatile and non-volatile flavour components and changes in cheese texture due to its metabolic action, resulting in the characteristic blue-green veined appearance. The veins are also responsible for the aroma of blue cheese.

The process of making blue cheese involves culturing a suitable spore-rich inoculum, such as P. roqueforti, and fermentation to maximise flavour. Sterilised, homogenised milk and reconstituted non-fat solids or whey solids are mixed with sterile salt to create a fermentation medium. A spore-rich P. roqueforti culture is then added, and modified milk fat is added to stimulate the release of free fatty acids through lipase action, which is essential for rapid flavour development.

Lipolysis, or the breakdown of fat, is a crucial step in the development of blue cheese's distinct characteristics. The lipase action triggered by P. roqueforti initiates the breakdown of fats, releasing free fatty acids. These fatty acids are then further broken down by the metabolism of the blue mould, forming ketones. This process gives blue cheese its richer flavour and aroma, contributing to its sharp flavour.

The blue-green veins of blue cheese are formed by the sporulation of P. roqueforti, which grows within the air tunnels created by piercing the aged curds. This fungus is adapted to thrive in dairy environments, tolerating cold temperatures, low oxygen levels, and both alkali and weaker acid preservatives. The mould grows along the surfaces within the cheese, creating the characteristic veined appearance.

The distinct sharp flavour, smell, and blue appearance of blue cheese are thus the result of the lipolysis triggered by P. roqueforti, which breaks down fats and forms ketones, enhancing the flavour and aroma, while the sporulation of the fungus creates the blue-green veins throughout the cheese.

Blue Cheese: A Safe Treat For Cats?

You may want to see also

The fungus thrives in dairy environments and is used to make many types of blue cheese

Blue cheese is made using a type of fungus called Penicillium, specifically Penicillium roqueforti, which is responsible for its distinct taste, smell, and appearance. P. roqueforti is the chief industrial use of this species and is used to make many types of blue cheese. The fungus thrives in dairy environments, and its growth leads to the production of volatile and non-volatile flavour components and changes in cheese texture due to the metabolic action of the species. P. roqueforti also triggers a biochemical event called lipolysis, which releases enzymes that catalyze the breakdown of fat and the creation of free fatty acids and methyl ketone, contributing to the cheese's distinct blue colour, sharp smell, and flavour.

P. roqueforti is added to the cheese after the curds have been drained and formed into wheels or injected into the curds before they form. The aged curds are then pierced, creating air tunnels in the cheese. When exposed to oxygen, the fungus grows along the surface of the curd-air interface, forming the characteristic blue veins of blue cheese. These veins are also responsible for the aroma of the cheese.

P. roqueforti is a genetically diverse species that can tolerate cold temperatures, low oxygen levels, and both alkali and weaker acid preservatives, making it well-suited for the dairy environment. It was first described by American mycologist Charles Thom in 1906 as a heterogeneous species of blue-green, sporulating fungi. The discovery of a sexual cycle in P. roqueforti has opened up the possibility of using sexual breeding to create new flavour profiles and other beneficial characteristics for cheese production.

The use of P. roqueforti in blue cheese production is carefully controlled to ensure food safety. While the fungus itself does not produce toxins and is safe for human consumption, improper storage of blue cheese can lead to the growth of other dangerous moulds, fungi, and bacteria. Therefore, it is important to store blue cheese properly in the refrigerator, tightly wrapped, to prevent spoilage and the potential risk of food poisoning.

Blue Cheese and Sulfites: What's the Connection?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The type of fungi in blue cheese is called Penicillium roqueforti.

Penicillium roqueforti creates the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese. It also gives the cheese its distinct smell and sharp flavor.

Unlike other types of mold, Penicillium roqueforti does not produce toxins and is safe to consume.