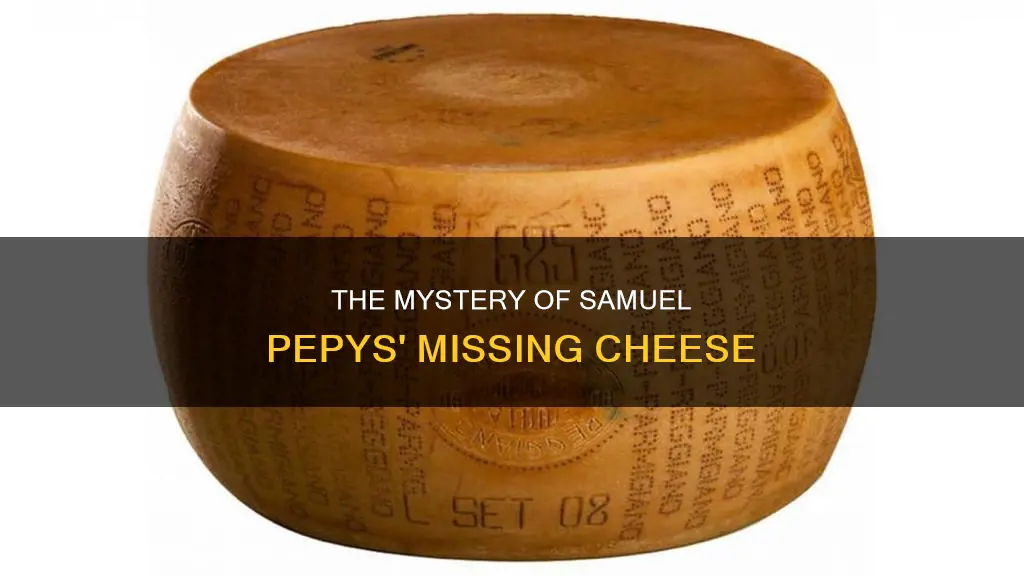

On 4 September 1666, Samuel Pepys, a renowned diarist and raconteur, was abruptly awakened by a servant informing him that a fire was rapidly approaching his home on Tower Hill. As the Great Fire of London raged nearby, Pepys and his servants frantically attempted to salvage his possessions. In a peculiar move, Pepys opted to bury his wine and Parmesan cheese in a hole he had dug in his garden. Parmesan cheese was a highly prized delicacy, often presented as diplomatic gifts. While Pepys' house survived the fire, he never documented the fate of his cherished cheese, leaving its recovery unknown.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | 4 September 1666 |

| Reason | The Great Fire of London |

| Location | Seething Lane, London |

| Food Item | Parmesan Cheese |

| Storage Method | Buried in a hole in his garden |

| Cheese Status | Fate remains unknown |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Samuel Pepys' house during the Great Fire of London

On the morning of Tuesday, 4 September 1666, Samuel Pepys was awakened by a servant, who informed him of a fire that had started two days prior on Pudding Lane. The fire was rapidly approaching Pepys' home on Tower Hill. Initially, Pepys told his servant to go away and returned to bed. However, he soon realised the severity of the situation and began evacuating his belongings.

Pepys' house and the Navy Office were not destroyed in the Great Fire of London. However, his birthplace in Salisbury Court off Fleet Street was burnt down. In his diary, Pepys mentions that he dug a hole in his garden and buried his wine and Parmesan cheese, indicating that he anticipated the fire reaching his home.

The Great Fire of London was a significant event that transformed the city's landscape forever. It started on 2 September 1666 in the premises of Thomas Farriner, the baker to the King. Within an hour, it had spread to the rest of the building, claiming the life of Farriner's maidservant. By the time it was extinguished, the fire had consumed approximately 13,200 houses, damaged four stone bridges (including London Bridge), and left an estimated 70,000 to 100,000 people homeless.

Pepys' diary provides a detailed and vivid account of the Great Fire of London, offering valuable insights into the event and the period. His descriptions of the fire and its aftermath have been praised for their historical significance, providing a unique perspective on the everyday life and challenges faced by the people of London during that time.

Get Iridium Cheese in Stardew: Ultimate Guide

You may want to see also

The fate of Pepys' cheese

On the morning of Tuesday, 4 September 1666, Samuel Pepys, a wealthy Englishman, was woken up by a servant who informed him that a fire that had started two days prior on Pudding Lane was fast approaching his home on Tower Hill. As the Great Fire of London raged on, Pepys and his servants rushed to save his belongings. In addition to packing up his money and personal effects, Pepys took the unusual step of burying his wine and Parmesan cheese in a hole he had dug in his garden.

Parmesan cheese was a highly valued commodity in the 17th century, often given as diplomatic gifts. For example, in 1511, Pope Julius II presented Henry VIII with 100 rounds of Parmesan cheese for aiding him in fighting the French. As such, it is not surprising that Pepys, a man of means, owned some Parmesan cheese.

The Great Fire of London was a catastrophic event that destroyed a significant portion of the city. Seventy thousand Londoners lost their homes, and the fire left a lasting impact on the city's landscape and history. Pepys' cheese, while a curious detail in the grand scheme of the disaster, stands as a reminder of the personal stories and losses that were woven into this tumultuous event.

The Hunt for Cheese in Once Human

You may want to see also

Parmesan cheese in the 17th century

On the morning of Tuesday, 4 September 1666, Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, was woken up by a servant who informed him that a fire had broken out two days prior on Pudding Lane in London and that his house was at risk. The Great Fire of London was fast approaching his home on Tower Hill. Pepys, however, chose to ignore the warning and went back to sleep. Later in the day, he buried his Parmesan cheese, wine, and other possessions in his garden to protect them from the fire. This incident provides valuable insight into the presence and significance of Parmesan cheese in 17th-century society.

Parmesan cheese, or Parmigiano Reggiano, is a hard, granular cheese produced from cow's milk and aged for at least 12 months, with some varieties aged for up to 36 months. Its name originates from the Italian provinces of Parma and Reggio Emilia, where it is traditionally made. The first mention of Parmesan cheese dates back to the Middle Ages when Benedictine and Cistercian monks crafted this long-lasting cheese using milk from cows raised on their farms and salt from the Salsomaggiore salt mines. By the 13th century, Parmesan had become a commercial product, appearing in Italian literature and legal documents.

During the Renaissance, local landowners in the Modena region began contributing to cheese production, enhancing its economic significance. By the 16th century, Parmesan had become a staple ingredient in the recipes of renowned cooks. Its popularity extended beyond Italy, as evidenced by Pope Julius II gifting Henry VIII 100 rounds of Parmesan cheese in 1511 for aiding him against the French. Parmesan was highly valued and often included in diplomatic gifts, making it a sought-after delicacy in the 17th century.

The production of Parmesan cheese has remained consistent over the centuries, with modern-day production still occurring in the same regions and utilizing the same ingredients. The process involves mixing the morning's whole milk with the naturally skimmed milk from the previous evening to create a part-skim mixture. The cheese is then aged, and each wheel is carefully evaluated to meet strict criteria to earn the official seal of approval. Parmesan has earned the nickname "King of Cheeses" due to its widespread appreciation, with historical figures like Napoleon, Moliere, and Alexandre Dumas known for their fondness for it.

In conclusion, the 17th century marked a significant period for Parmesan cheese, with its presence in England evidenced by Samuel Pepys' possession and its continued popularity among the aristocracy and gourmands. Parmesan's enduring appeal and cultural significance have contributed to its enduring legacy, solidifying its place as a renowned cheese variety.

Real Cheese: Where to Source the Best

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pepys' diary entries about the fire

On the morning of Tuesday, 4 September 1666, Samuel Pepys was woken by a servant, warning him about a fire that had started two days earlier on Pudding Lane. Pepys initially went back to sleep, but later that day, the reality of the situation hit him, and he began to remove his belongings from his house.

> Up by break of day [we can that with a pinch of salt] to get away the remainder of my things; which I did by a lighter at the Iron gate and my hands so few, that it was the afternoon before we could get them all away.

In his diary entry for 4 September, Pepys describes walking down to Tower Street, where he witnessed the fire's ferocity first-hand. He also mentions the practice of blowing up houses to stop the fire from spreading, which initially frightened people more than anything else.

> Now begins the practice of blowing up of houses in Tower-streete, those next the Tower, which at first did frighten people more than anything, but it stopped the fire where it was done, it bringing down the houses to the ground in the same places they stood, and then it was easy to quench what little fire was in it, though it kindled almost nothing.

Pepys also notes the impact of the fire on individuals, such as W. Hewer, who had to move his mother to Islington due to her house in Pye-corner being burned down.

On the same day, Pepys and Sir W. Pen dug pits in their garden to store their wine, important papers, and other valuables, including Pepys' Parmesan cheese.

> Sir W. Batten not knowing how to remove his wine, did dig a pit in the garden, and laid it in there; and I took the opportunity of laying all the papers of my office that I could not otherwise dispose of. And in the evening Sir W. Pen and I did dig another, and put our wine in it; and I my Parmazan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.

The Great Fire of London, as it came to be known, destroyed much of the city, including areas west of Bethnal Green and the Tower. Pepys dined with friends in Woolwich, and they could see the fire raging across the city from their garden.

> Only now and then walking into the garden, and saw how horridly the sky looks, all on a fire in the night, was enough to put us out of our wits; and, indeed, it was extremely dreadful, for it looks just as if it was at us; and the whole heaven on fire.

Pepys' diary entries provide a detailed and personal account of the Great Fire of London, capturing the chaos, destruction, and his own efforts to protect his belongings.

Applebee's Three Cheese Chicken Penne: Gone for Good?

You may want to see also

Pepys' reasons for burying his cheese

On the morning of Tuesday, September 4, 1666, Samuel Pepys was awakened by a servant who informed him that a fire that had started two days earlier on Pudding Lane in London was approaching his home on Tower Hill. This was the Great Fire of London, which threatened to destroy Pepys' house.

Faced with the impending disaster, Pepys took steps to safeguard his belongings. He packed up his money and other personal effects, and dug a hole in his garden to store his wine and Parmesan cheese, which was expensive and highly valued at the time. Parmesan cheese was a sought-after delicacy and was often given as diplomatic gifts. It was also valuable objectively, as it was worth a great deal of money. Pepys wrapped his cheese in several layers of protection, including plastic, cling film, cloth, and tinfoil, in an attempt to keep it safe from the elements.

The fate of Pepys' cheese remains a mystery, as there is no record of whether it was recovered or if it fell victim to the fire or worms. However, the act of burying valuables to protect them from impending danger is a well-documented practice throughout history. For example, the Watlington Hoard, a collection of coins, is believed to have been buried during the retreat of the Vikings to protect it from potential loss.

Pepys' decision to bury his cheese can be understood in this context of safeguarding valuables. He recognized the cheese's monetary and personal value and took steps to protect it from the impending fire. By burying it in his garden, Pepys likely hoped to retrieve it once the danger had passed, ensuring the preservation of this valuable commodity.

In conclusion, Samuel Pepys' reasons for burying his cheese during the Great Fire of London can be attributed to its monetary and personal value. By taking steps to protect it, Pepys demonstrated his priorities and ensured the preservation of a valuable asset. While the fate of the cheese remains unknown, the act of burying it reflects a broader historical practice of safeguarding valuables during times of disaster or uncertainty.

Swiss Cheese Holes: A Mystery Solved

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Pepys buried his Parmesan cheese in his garden during the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Parmesan cheese was a particularly sought-after food item at the time, commonly used as diplomatic gifts. It was produced from skim milk and aged for two years.

Pepys' house survived the fire, and it is thought that he recovered his cheese. However, he never recorded the fate of his cheese in his diary, so its fate remains unknown.

Pepys buried his wine and important papers alongside his cheese.